|

|

|

SHARK INFO |

|

SHARK |

|

SHARK EVOLUTION |

|

|

|

SHARK DIVING |

|

SHARK DIVING 101 |

|

|

|

CONSERVATION |

|

|

|

PHOTOGRAPHY |

|

SHARK PHOTO TIPS |

|

|

|

RESOURCES |

|

|

|

WEB STUFF |

|

WHAT IS ELASMODIVER? Not just a huge collection of Shark Pictures: Elasmodiver.com contains images of sharks, skates, rays, and a few chimaera's from around the world. Elasmodiver began as a simple web based shark field guide to help divers find the best places to encounter the different species of sharks and rays that live in shallow water but it has slowly evolved into a much larger project containing information on all aspects of shark diving and shark photography. There are now more than 10,000 shark pictures and sections on shark evolution, biology, and conservation. There is a large library of reviewed shark books, a constantly updated shark taxonomy page, a monster list of shark links, and deeper in the site there are numerous articles and stories about shark encounters. Elasmodiver is now so difficult to check for updates, that new information and pictures are listed on an Elasmodiver Updates Page that can be accessed here:

|

|

_ |

River Stingrays |

|

River Stingrays: Two color morphs of Potamotrygon castexi

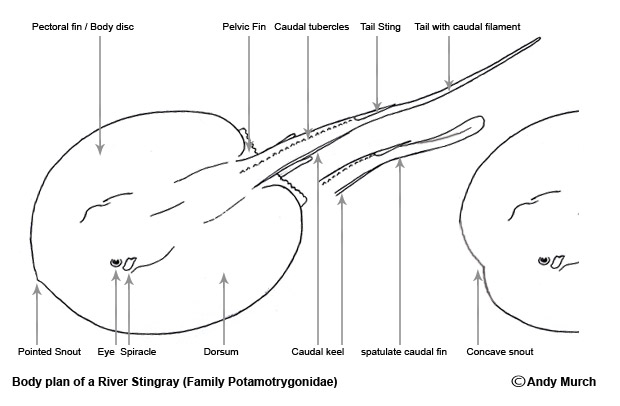

River Stingrays The family Potamotrygonidae which is commonly referred to as the River Stingrays is in dire need of revision. There are presently 3 valid genera a one that has not been scientifically described but contains a ray that is visibly different enough to warrant a separate classification. There are at least 22 species although identification is extremely difficult in this unusual family group. Below is a key to the genera of River Stingrays:

Identifying Individual Species

If you though identifying marine stingrays was difficult, try determining

the exact species of a River Stingray. Body

Although the problem of polychromatism implies that positive i.d. just

from coloration alone is almost impossible, there are species that display

distinct color morphs not shared with any other species. Also, some

characteristics among similar patterned species are more telling than it

would at first appear. For example, Potamotrygon castexi can

exhibit a large variety of patterns but they tend to fit within a certain

range that blend into each other. When these patterns are considered along

with other characteristics it often becomes possible to narrow down the

species with reasonable certainty.

To help classify River Stingrays that are traded among aquarists, a more

detailed (but also more subjective) classification system has been

developed that splits up the recognized species into their various color

morphs. In this system, our example P.castexi is further split by

appearance into Jaguar Ray, Estrella Ray, etc. but although this works for

aquarists it is difficult to follow when translated between languages as

it does not have a universal Latinized equivalent and it serves no real

purpose to taxonomists unless two morphs are eventually identified as

separate species.

Once the genera has been ascertained, the best key to species

identification (apart from DNA testing) is the markings on and shape of

the tail.

Habitat and Geographic Distribution

River Stingrays are distributed throughout most of the tropical river

systems of South America. They comprise the only elasmobranch group that

is completely adapted to living exclusively in fresh water.

Brazil contains the greatest number of species (around 18) but

potamotrygonid rays can also be found in Argentina, Bolivia, Columbia,

Ecuador, French Guyana, Guyana, Paraguay, Peru, Surinam, Uruguay, and

Venezuela. P.motoro which is the most common River Stingray has

been reported from all of these countries except Ecuador.

River Stingrays can be found in rivers with sand, mud, or stony bottoms.

During the rainy season they also move into areas of flooded forest.

River Stingrays spend a percentage of their time buried under the sand or

mud with just their eyes protruding.

Freshwater Modifications

River Stingrays have developed permanent modifications to adapt to the

freshwater environment that they are confined to. One significant

modification is the degeneration of the rectal gland that serves in the

excretion of excess salt in marine elasmobranches. Salt water rays also

have the ability to retain high levels of urea in their blood which

counters the osmotic flow of fluids through their skin into the salt rich

water. River Stingrays have lost this characteristic resulting in an

inability to tolerate environments with a salinity greater than 3 ppt.

The electroreceptive ampullae of Lorenzini among River Stingrays is also

modified to operate in freshwater.

Reproduction

River Stingrays practice a style of reproduction known as matrotrophic

viviparity. Villi (umbilical filaments) are formed that nourish the

fetuses while in the uterus. The reproductive cycle has been shown to

coincide with hydrological changes in the rays environment. Gestation can

last between 3-12 months with 1-8 embryos in gestation at one time.

Diet

River Stingrays eat a wide variety of available foods from worms to insect

larvae, shrimp and other tiny crustaceans, and small fishes. Most of their

food is located in the sediment and literally sucked in. Their tooth

structure like other stingrays consists of small rounded molars that form

a flat upper and lower surface designed to grip but not cut.

Defensive Mechanisms and Treatment of Stingray

Wounds

River Stingrays carry one or more stingers or tail spines on the

top of their tails. This weapon is capable of puncturing the hide of a menacing

predator or impaling the leg or abdomen of a wading fisherman. It is sheathed in a mildly venomous covering of skin which is

pushed back as the point enters the victim allowing the venom to come in

contact with the cut tissue. Wounds inflicted by these stingers are

apparently very painful but the toxins can be broken down quickly with

heat. Treatment of a stingray wound should involve immersing the affected

area in water as hot as the victim can tolerate. The wound should also be

irrigated to ensure that no part of the spine has broken off. Infections

are common and where medical attention is not readily available River Stingray wounds

have resulted in fatalities. In the Amazon the River Stingray is highly

feared among the natives that work along the river.

The Aquarium Trade

For the most part River Stingrays are at the top of the food web

especially far up river where Bull Sharks are less likely to penetrate.

The greatest threat that they face is removal by collectors for export

into the aquarium trade. This has become a major problem but recently

exports from Brazil were halted while a quota system is implemented.

Fortunately for the stingrays, their cryptic appearance has led to so much

difficulty identifying specific species that none can be exported until a

better i.d. system is figured out. As DNA testing for aquarium collectors

is impractical it may be many years before this hurdle is overcome. Under

the right conditions River Stingrays will mate in captivity and many

animals for sale now come from captive breeding programs. Interestingly,

because species from different geographic regions are often housed

together this has led to even more hybrids joining the melting pot.

Locomotion

River Stingrays are able to swim forwards (and slowly backwards) by

undulating their pectoral fins that form their body disc. See:

Elasmobranch Locomotion. Their

tails with their rudimentary caudal fins are used for steering and balance

and also to support their defensive tail stings.

Breathing

River Stingrays spend a percentage of their time buried with just

their eyes showing. Their mouths and gills (like almost all rays) are

positioned under their bodies which makes breathing while on the sand

rather challenging. To overcome this hurdle they have developed large

spiracles (spiracles are the openings positioned just behind the eyes

through which a shark or ray can suck in oxygen rich water to flush over

the gills). Through this mechanism River Stingrays are able to remain

motionless for hours at a time.

River Stingray Evolution

It is unclear which group of marine rays the Potamotrygonidae evolved from

but there are two main theories:

It was initially thought that an invading species of himantura (one of the

whiptail stingray genuses) colonized the Amazon Basin from the Atlantic

(Garman, 1913, Bigalow and Schroeder, 1953). Geographically this makes

sense because the sprawling mouth of the Amazon is unprotected by rapids

or other features that would protect it from invasion. Whiptail stingrays

are also commonly found in estuarine environments and are euryhaline -

able to tolerate fresh water for long periods.

The second theory based on parasitological evidence has River Stingrays

evolving from the Urolophidae (a family of round stingrays confined to the

Pacific) that were trapped during the creation of the Isthmus of Panama

(Brooks et al., 1981). Parasitological evidence (comparative

analysis of the parasites living in the gut and other areas with the body

of an animal) is considered to be quite significant in evolutionary terms

but apart from this characteristic River Stingrays have little in common

with Round Stingrays as the latter are confined to saltwater environments.

Instead, an Indo-west Pacific Whiptail Stingray (Taeniura lymma or one of

its predecessors) may be the most likely ancestor of the River

Stingray.

|